19 November 1414: the announcement of plans to invade France

By Dan Spencer

It was at the parliament held at Westminster between 19 November and 7 December 1414 that plans to invade France were first made public.

Parliaments in this period always began with an opening speech which set the tone and explained why the king had summoned a parliament. On 19 November 1414 Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester and Chancellor of England, in the Painted Chamber of Westminster Palace, addressed the assembled lords and commons in the presence of the king. A summary of what he said is recorded in an official account known as the Parliament Roll.

And then the same chancellor, at the king’s command, pronounced the reason for the summons of the said parliament, declaring at the start how our most sovereign lord the king desires especially that good and wise action should be taken against his enemies outside the realm, and furthermore how he will strive for the recovery of the inheritance and right of his crown outside the realm, which has for a long time been withheld and wrongfully retained, since the time of his progenitors and predecessors kings of England, in accordance with the authorities who wish that ‘unto death shalt thou strive for justice’, and ‘that which is altogether just shalt thou follow’: to accomplish which most honourable purpose it is necessary to provide for many things, which the said chancellor then explained through many authorities and notable passages; and he took for his theme, ‘As we have therefore opportunity, let us do good unto all men’

The chancellor then went on to say

The king our most sovereign lord, considering the benefits of peace and tranquillity reigning at present by God’s great gift throughout all his realm, as everyone is well aware, and also the truth of his quarrel in this matter – which are the most necessary things for each prince who has to make war on his enemies abroad – understands that a suitable time has now come for him to accomplish his said purpose with the aid of God, and thus, ‘while we have time let us work for good’. But in order to bring that high and honourable purpose to a good end, he said that three things are especially necessary: that is, wise and loyal counsel from his lieges, powerful and true aid from his people, and a generous subsidy of money from his subjects.

Those listening to the speech had been summoned to parliament by royal writs issued on 26 September. ‘The lords’ were men who had received an individual summons: these were the titled nobility as well as the bishops and the leading abbots. ‘The commons’ were men elected by the leading members of their communities (universal suffrage did not exist at this time). Each county in England elected two representatives (known as ‘knights of the shire’, although they did not need to be dubbed knights) and the leading towns also sent two representatives (‘the burgesses’). For the parliament of November 1414 we know the names of all 76 knights of the shire and of 176 burgesses.

Several of the knights of the shire sitting in this parliament were to serve on the 1415 expedition, as were the majority of the nobility. The Speaker selected by the Commons was Thomas Chaucer (son of the poet Geoffrey Chaucer). In April 1415 he contracted to provide 12 men-at-arms and 36 archers for the campaign but was ill and does not seem to have crossed to France.

Why did Henry V need to call a parliament in order to go to war? Although kings of England had absolute control over foreign policy they needed to have the assent of the Commons to taxation: this dated back to the late thirteenth century. On this occasion the Commons agreed to a double lay subsidy to be collected in two instalments (2 Feb. 1415 and 2 Feb. 1416). On the back of this guaranteed income, the king could start to raise loans.

Parliament offered an opportunity to generate a sense of national investment in the war. We must imagine the knights of the shire and burgesses (the term member of parliament was not in use yet) going back to their communities and publicising the king’s intentions. So the road to Agincourt really starts at the parliament.

This information came from ‘Henry V: November 1414’, Parliament Rolls of Medieval England. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=116520 Date accessed: 14 November 2014; A. L. Brown, The Governance of Late Medieval England 1272-1461 (London: Edward Arnold, 1989), pp. 175-185; ‘Chaucer, Thomas (c.1367-1434), of Ewelme, Oxon’, in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1386-1421, J. S. Roskell, L. Clark, C. Rawcliffe (eds) (Woodbridge: Boydell, 1993)

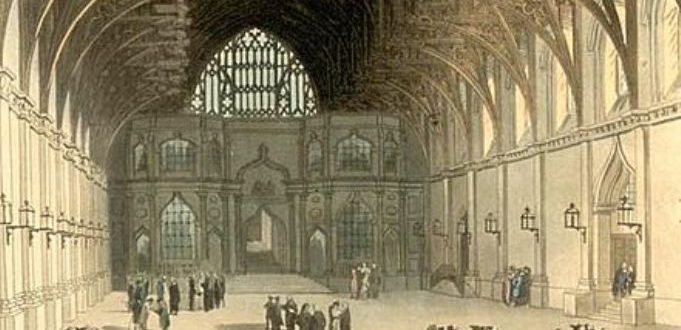

Picture of Westminster Hall in the early nineteenth century came from Wikipedia and is in the Public Domain